SUMAYA SHIHAB

It usually takes a generous stretch of time to create something brilliant. From the spark of an idea to early drafts, to the refining and final touches, many artists spend weeks, months, or even years bringing their work to life—whether it’s a book, a painting, a film, or a research paper. Yet, on occasion, inspiration strikes in the span of minutes.

Paul McCartney once woke up with the melody of “Yesterday” in his head. Charlie Puth wrote “See You Again” in ten minutes. J.K. Rowling conceived Harry Potter on a train ride. These moments seem magical, but as Saudi writer and performer Muhammed Al-Farra puts it, “Inspiration is that shy guest—sometimes it visits, sometimes it doesn’t.”

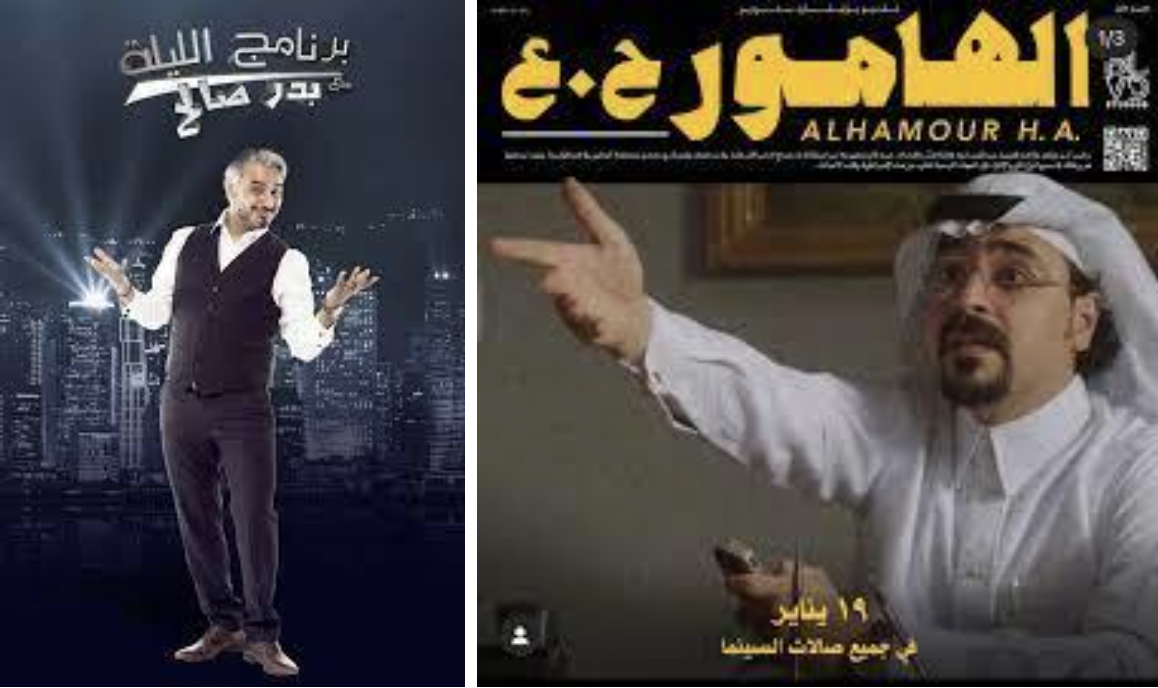

Saudi writer and performer Muhammed Al-Farra

Should writers wait for it to arrive? “Relying on inspiration can become a trap,” Al-Farra warns. For him, true creativity comes from consistent effort, not luck. “A skilled writer should be able to create anytime, with quality.”

Muhammed Al-Farra’s contribution to the Saudi TV show Al-Laylah Ma’ Badr, and a poster featuring him as an actor in The Tambour of Hamour (Alhamour H.A.), a Saudi film selected as Saudi Arabia’s official submission for the Oscars.

In Western culture, success often centers on the outcome. In Arabic, however, najah means achieving a goal, while falah—a concept with no direct English equivalent—values the process itself. In Arabic literature and thinking, luck plays little role; discipline and perseverance are what truly matter.

Writers’ Inspirations & Values

The journey of writing is often intertwined with many aspects, such as the writer’s culture, memory, history, beliefs, and personal identity. For Monther Al-Kabbani, a Saudi surgeon turned novelist, whose seven Arabic language novels (many of which have been translated into other languages) explore themes “related to questions about life, reality, and conventional beliefs…although history plays a role.”

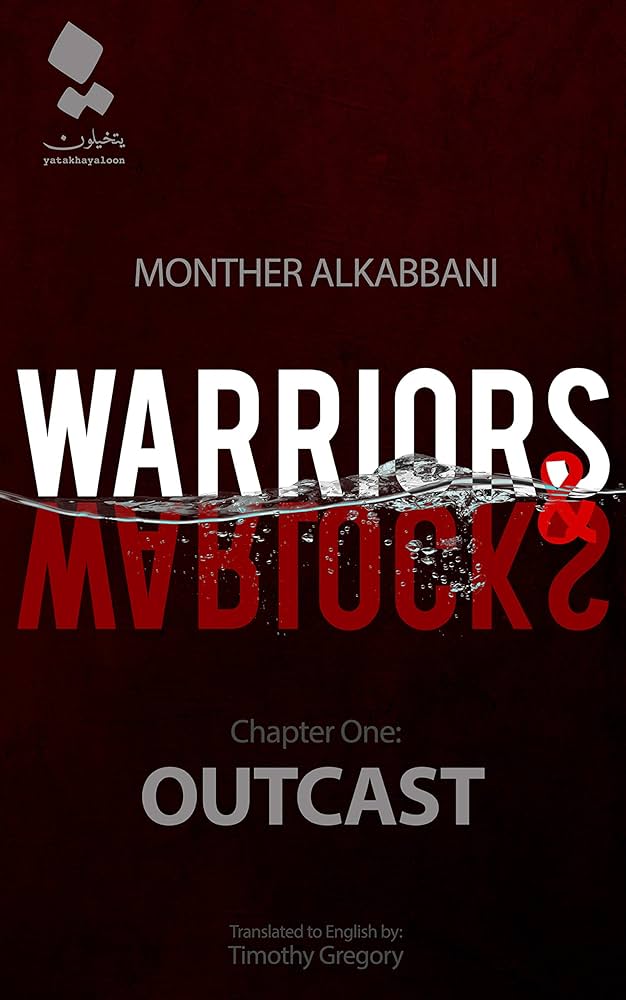

Novelist Monther Al-Kabbani

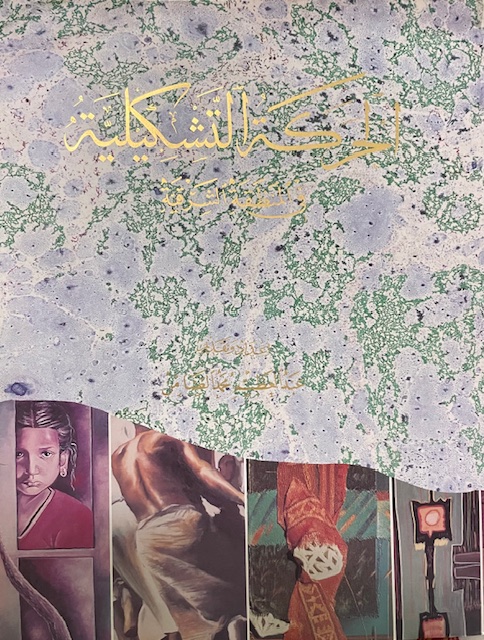

The writing journey, on another hand, for Abdulathim Al-Dhamin, a Saudi visual artist, writer, and passionate advocate for the Saudi Fine Arts and Cultural Movement, “take(s) two paths: one that’s grounded in research and study, and another that flows more intuitively. For instance, when (I) wrote The Visual Art Movement in the Eastern Province, it required over two years of source-gathering and verification, but novels like Jouri and Malak were very different. These emerged from within—fiction intertwined with truth, which is what gives novels their unique literary spirit.”

Visual artist and writer, Abdulathim Al-Dhamin

And yet, for Turki Al-Dakhil, former Saudi Ambassador to the UAE, renowned journalist, and author, who reflects on his return to the literary world after years of diplomatic service, inspiration came from moments that have stayed with him, like many of us (writers or otherwise). “One (conversation) that I often return to is my interview with the late King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, may God rest his soul…As a journalist, I was trained to look for headlines, but as I matured in the profession, I came to see that the real story often lies in the subtleties—the pauses, the hesitations, and the emotion behind what is said and unsaid.”

Renowned journalist, and author, Turki Al-Dhakil

Al-Dakhil, drawing from his diplomatic and literary experiences, expands the conversation from personal inspiration to a broader reflection on the values a Saudi writer can bring to the world today. When asked about this, he shared: “Our writers and artists are uniquely positioned—they stand at the crossroads of deep-rooted traditions and sweeping transformation. The values they can offer are many: a sense of continuity in the face of change; a belief in community and shared identity; a celebration of hospitality, resilience, and faith…They can offer a message of complexity—that we, too, contain contradictions, debates, humor, and hope…And that, to me, is a rare and precious thing.”

From The Writer

One notable observation from our conversations with the writers is that none of them introduced themselves solely as a writer, which tells something. Writing, after all, demands to be nourished—by experience, by habits, by community. For each of the authors we feature here, writing is an integral part of their lives, but never the entirety. Their work spans a wide range of fields: economics, academia, visual arts, media, research, poetry, and even public speaking.

Interestingly, Al-Dakhil reflects on this balance between life and writing, particularly during his time serving as Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the UAE: “During my years as ambassador, my official duties and diplomatic responsibilities took precedence, and understandably, I wrote far less in the public sphere. But in private, the pen never left my hand—or rather, my thoughts never ceased to seek expression.”

To the Audience

If writing is born from life experiences, it ultimately lives in the hearts of its readers. After all, once a writer shapes their words, those words seek a home beyond the writer’s own mind. This brings us to a critical question every writer must face: Who is this for? We asked the writers how they view this relationship between writing and audience.

For Al-Kabbani, the approach is simple and inclusive: he “writes for anyone who wants to read something enjoyable and thought-provoking, regardless of their religion or ethnicity.”

Al-Farra, who comes from a background in screenwriting and digital content creation, adapts his voice to each project: “Even before the idea for a project takes shape, (I) focus on understanding the target audience. (My) tone and narrative approach always shift depending on who (I)’m writing for. The goal is to make sure the message truly lands with the viewer or reader.”

For Al-Dhamin, the starting point is always the work itself—its essence and integrity. But when he senses a piece has broader appeal, he consciously writes “with all readers in mind.” One memorable experience reinforced this belief: “When I wrote Jouri, it reached readers in Italy. A colleague there read it and asked to translate it into Italian. That moment reminded me how literature can be a cultural bridge—how our stories can travel and speak to others across languages.”

The Question of Saudi Identity

Building on Al-Dhamin’s reflection on how literature becomes a cultural bridge, the question of Saudi identity naturally rises to the surface.

For decades, Western cinema—and even Eastern cinema—has painted an outdated and narrow picture of Saudi Arabia: “a desert-dweller surrounded by camels, oil wells, and submissive women.” In contrast, Al-Dakhil notes, “the millions of pilgrims, visitors, and now tourists who come to Saudi Arabia each year contribute organically to cultural diplomacy. They witness and share the authentic Saudi story—one of diversity, kindness, and depth.”

Saudis believe it’s their responsibility—not that of visitors—to present their identity to the world in their own voices. Whether emerging or established, writers see it as a shared duty to reshape perceptions of Saudi Arabia through ongoing effort, not luck—an approach rooted in the concept of falah.

On the subject of global perceptions and Arab identity, Al-Dakhil adds: “Arab identity is not monolithic. It is a mosaic—geographically, linguistically, culturally. Literature and art help preserve this complexity. They give voice to the forgotten, the marginalized, and the visionary. Whether it’s the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish, the films of Youssef Chahine, or the novels of Ghassan Kanafani, these works challenge stereotypes and show that we are not the caricatures drawn by others. At the same time, contemporary Saudi literature and visual arts are thriving. I’ve seen firsthand how young Saudi artists, writers, and filmmakers are using their craft to speak not just to the world, but to themselves—to question, to reclaim, and to imagine. This is perhaps the most powerful form of diplomacy: when a nation tells its story on its own terms.”

Al-Dhamin deepens this view by pointing to another essential aspect of cultural preservation: the language itself. “We owe it to our readers and to the Arabic language to be diligent. That’s why we run our work by multiple proofreaders before publication—to ensure clarity and uphold the language’s beauty.”

While it can be tempting to adapt to international audiences by imitating global styles, Saudi writers should recognize the importance of staying true to their roots. Al-Farra emphasizes: “I always remind myself and others in the field that we carry a responsibility. Our identity, language, and heritage are what set us apart… That doesn’t mean we can’t create stories for a global audience; It just means that our Saudi fingerprint must always be visible in what we present to the world.”

This responsibility cannot rest on individuals alone, Al-Dakhil concludes. Contributing to the preservation of Saudi cultural identity amid the rapid regional and global changes is a “mission (that) cannot be accomplished by a single entity—no matter how powerful or influential. It requires the combined efforts of numerous institutions and individuals.”

Writers’ Challenges & Opportunities

The responsibility of preserving identity through writing, while remaining authentic to one’s roots, brings with it a unique set of challenges and opportunities for Saudi writers today. As our featured writers suggest, the evolving literary landscape in Saudi Arabia is rich with possibility, yet demands careful navigation. New voices continue to emerge, and it is their individuality and authenticity that set them apart. Both Al-Farra and Al-Dhamin, echoing each other’s thoughts, call this “a golden age for Saudi creatives.”

Al-Farra elaborates: “Content creation, in all its visual and auditory forms, is booming. What’s exciting is how this era has made space for talents both inside and outside traditional literary circles. Those with academic backgrounds share their knowledge, while newcomers bring fresh approaches and innovation.” Al-Kabbani also notes the rapid momentum:“The literary scene in Saudi has evolved quite rapidly over the last 20 years. The novel has taken centre stage, and there is currently extra recognition of the importance of literature in the cultural exposure of Saudi under Vision 2030… especially for the new voices who have something unique to offer.”

Al-Dhamin agrees, pointing out that “today’s emerging writers are receiving unprecedented support from the Ministry of Culture,” and that the scene indeed “has been evolving since the 1970s, but the past five years have seen a remarkable acceleration. Book fairs became sanctuaries for writers and readers alike, and many voices that had long gone unnoticed finally found their stage. Literary forms of all kinds—poetry, storytelling, criticism—have flourished.”

From an insider’s perspective on how this evolving scene unfolded, Al-Dakhil reflects: “We are still in the transitional phase, in which most of its components are being shaped through experience and practice. For example, the abundance of cultural activities and events in Saudi Arabia has created a need for a large number of managers to oversee these events—something that wasn’t required when the cultural events were fewer before this transformation. The demand for these coordinators and moderators for seminars, lectures, and discussions led to the inclusion of young people without prior experience in this field. Some of them performed poorly, which is natural, but others presented stunning and surprising models for everyone. Through these experiences, a group was trained for this task, and the sector gained professionalism and expertise in creating a cultural role that it didn’t have before.”

Of course, with opportunity comes challenge. Al-Kabbani points out a persistent obstacle: “It is still finding a publisher who is willing to take a risk with a new, unknown writer, and the lack of literary agents who can help a new writer to start his (or her) journey.” Meanwhile, Al-Dakhil identifies a more systemic concern: “Dealing with the rapid pace that has become a characteristic, form, and substance of all modern communication platforms…If the focus on speed exceeds the emphasis on the quality of the media content, or on verifying its accuracy, or on enhancing it with supporting information, stories, and so on, it will have negative consequences for the media work as a whole, affecting the credibility, efficiency, value, and weight of the content.”

Final Thoughts

To you, who are emerging in the field of content creation in Saudi Arabia, we leave you with some food for thought from writers who have walked the path before you.

“Don’t be afraid to ask questions and seek answers to them; Be prepared to find surprises while on that journey. Accept the truth no matter how hard you may find it, and do not let preconceived notions blind your judgement.” – Al-Kabbani

Al-Dhamin recounts his own journey in writing, reminding you that writing is not a solitary achievement, but rather a unique blend of dedicated efforts, support, and patience. He credits the country’s role as well as those who offered constructive feedback and the encouragement of his graduation supervisor. He began writing his novel in 2006, only to set it aside 3 years later, feeling “unsatisfied and worried how society might perceive it.” A decade later, he started anew with Jouri, which saw publication in 2023. His second novel, Malak, followed in 2025. His is clearly not a journey of overnight success.

And, if you are still wondering how all of this relates to your own steps forward, Al-Farra offers a simple, timeless reminder: “At the end of the day, whether you’re inside or outside the literary framework—you’re still a storyteller. And storytelling is human nature.”

These Saudi voices affirm that to write, to create, to tell your story, is not just a career, it’s a calling. And as Saudi Arabia continues to shape its narrative on its own terms, there has never been a more important time to pick up the pen.

GET TO KNOW THE WRITERS:

Monther Al-Kabbani: instagram.com/montheralkabbani

Muhammad Al-Farra: instagram.com/xfarra

Turki Al-Dakhil: instagram.com/turkialdakhil